By Jerry Jenkins, NFA 6/21/16.

Tips for identifying white oaks…

Oaks are best identified by acorns and leaves; buds and bark also work, but are less decisive. They divide into the black oaks, with bristle-pointed leaf lobes and bumpy scales on the acorn caps, and the white oaks without bristles. This post shows the six white oaks of the northern forest and the characters I find most useful for identifying them.

When comparing the photos, please realize that leaf shape varies greatly, even sometimes wildly, within a single species. The shape is at best a general guide; the critical leaf characters are the presence and absence of different kinds of hairs on the lower side. A lens of about 20 power or microscope is required for this.

The oaks are a southern group, and none of them occur throughout the Northern Forest Region. None the less, all but the highest and most northern parts have at least one oak, and the southern parts, like the Taconics where I live, may have nine or ten.

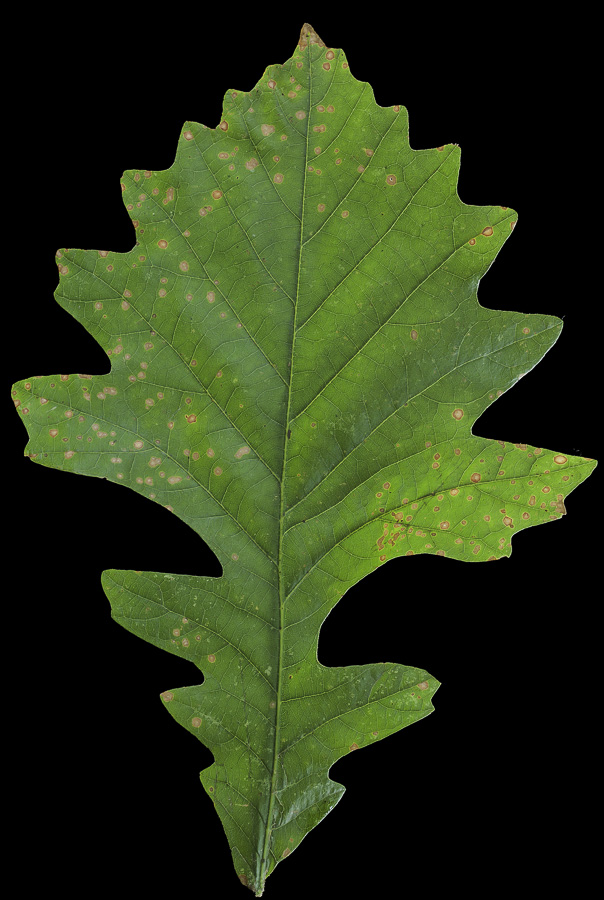

The white oak itself, Quercus alba, is the most widely distributed of the white oak group in the NFR, but always at low elevations, and often on dry, rocky or sandy soils. It is recognized by (1) the hairless, deeply lobed leaves with rounded lobes and a whitened lower surface; and (2) the small acorns with bumpy, furry scales. The new twigs are smooth and often whitened, and the buds short and rounded.

White oak leaves vary from shallowly lobed to deeply lobed. The deeply lobed ones are distinctive; the shallowly lobed ones are similar in shape to some swamp white oak leaves. The whitened undersides are a reliable separation. The small rounded buds and short, small acorns resemble those of several other species, particularly yellow oak and dwarf chestnut oak. I am not sure there is a reliable separation for either..

The swamp white oak is a floodplain species, frequent in the southern parts of the Northern Forest Region, always at low elevations. The leaves have rounded teeth or shallow lobes, and minute stellate (multibranched) hairs on the lower side. Note that there are a few weal veins that run to the notches, or peter out before reaching an edges. The buds are short and rounded, and there are often stipule remnants—small, skinny, shriveled things—within the cluster of terminals buds. The acorns are on long stalks, and are distinctive. Unfortunately the trees in my area don’t fruit very often and I have no pictures.

Swamp white oak leaves need to be separated carefully from white oak (whitened below, more deeply lobed) and chestnut oak (all veins run to lobes, long hairs along the veins below). The buds are not very distinctive by themselves, but the combination of short rounded buds and bark that starts to crack and flake off the older branches is a good character.

The burr oak is a common species in the western parts of the Northern Forest Region, and in fact the dominant tree on dry hills where the forest opens up into prairie. It is rarer eastwards, and less ecologically predictable, but found in scattered populations all the way east to Maine and New Brunswick. The leaves and acorns are distinctive. The leaves are typically broad and shallowly lobed above the middle, and narrower and more deeply lobed below. No other oak in our range looks like this. The acorns are large and shallow, with a curly fringe to the edges of the cap. Our trees here in the Taconic only fruit rarely, and I have no pictures. The buds are short and rounded, rather typical for white oaks, but the twig tips are minutely hairy, there are often stipule remnants among the tip buds, and the older branches develop corky ridges. Some combination of these features will usually identify trees in the winter, though finding a few old leaves is often easier.