Jerry Jenkins, August 2016

This week, I was photographing sedges at Branch Pond, in the southern Green Mountains. There are about 24 species in the pond and the woods and wetlands around it. My goal was to show them as a field biologist sees them—in their natural settings, and with the features that distinguish them.

This has not been done that often. The sedges are a technical group, and with technical groups the tendency is to focus on, and identify them by, small details of their flowers and leaves.

But the sedges are also a conspicuous and distinctive group. Especially in the north, where ecological patterns are strong, they occur in predictable places and have predictable growth forms and associates. Often these, or these plus a few technical details, are plenty enough to identify them.

One of goals of the Atlas project is to illustrate ecological patterns. Branch Pond is a good place to start, because the patterns are strong there. And the sedges are a good group to start with, because they are conspicuous, challenging, and responsive to those patterns.

About Branch

Branch Pond is located on the southern Green Mountain Plateau at an elevation of 2,600 feet. The rocks are old and infertile. The land is gently rolling and the soils are thin, peaty, and wet. The forests, which are young and much logged, are dominated by spruce, fir in the basins, northern hardwoods on the hilltops, and mixtures in between.

Wetlands—the greener and finer-textured areas in the air photo— are large and common. Before the return of the beaver, which began around 1950, many of these wetlands were conifer swamps or boggy meadows. The beaver converted many of them to open meadows, but left conifer swamps in the basins without dammable outlets, and bog mats around the shores of lakes and ponds. They likely left boggy fringes around some of the beaver meadows.

Here is a simplified map of the pond.

Currently there seem to be more beaver meadows than active beaver colonies. The boggy fringes have expanded, and many of the beaver meadows now are are a blend of meadow and bog vegetation. They have the channels, snags, alder, and tall grasses and broad-leaved sedges of beaver meadows, but the hummocks, sphagnum mats, evergreen shrubs, and narrow-leaved sedges of bogs. I call them beaver-bogs. A generalized ecological diagram of one of the ones near Branch looks like this.

In this article, I show the woodland and boggy-meadow sedges. In the next, I will show the pond-shore and floating-bog sedges.

Sedges in the woods

On my first trip, I photographed sedges along the Bourne Pond trail and in the East Meadows. I illustrate them here, showing you first the ecological photos and then, from the studio and mostly earlier in the year, the details of the fruits.

Trails are good places for sedges. They like the light and the water, and may disperse along them.

Here, for example, is a double band of Carex debilis (= weak or leaning, from the arching stems) on the Bourne Pond trail.

Debilis is one of the commonest sedges in cool, relatively infertile woods. It is clump forming, with long, medium-width, leaves with red on their sheaths. Carex intumescens, also very common in the same woods is quite similar, and difficult to distinguish vegetatively, though its ligule is often more round.

The safest distinctions are the flowering stems and fruits. Debilis has long arching flowering stems, and slender fruits (perigynia) in elongated clusters.

Intumescens has shorter, leafier stems, with inflated perigynia in small clusters.

Another very common woodland sedge, characteristic of cold, moist woods, is Carex brunnescens. It commonly grows along trail edges; here it is next to a rock.

Here it is in a small wet hollow.

On forest soil, as here, the long, slender leaves are a good presumptive identification.

On peat, however, the commonest narrow-leaved species is Carex trisperma. Here is trisperma in the understory of a cedar swamp in central Vermont.

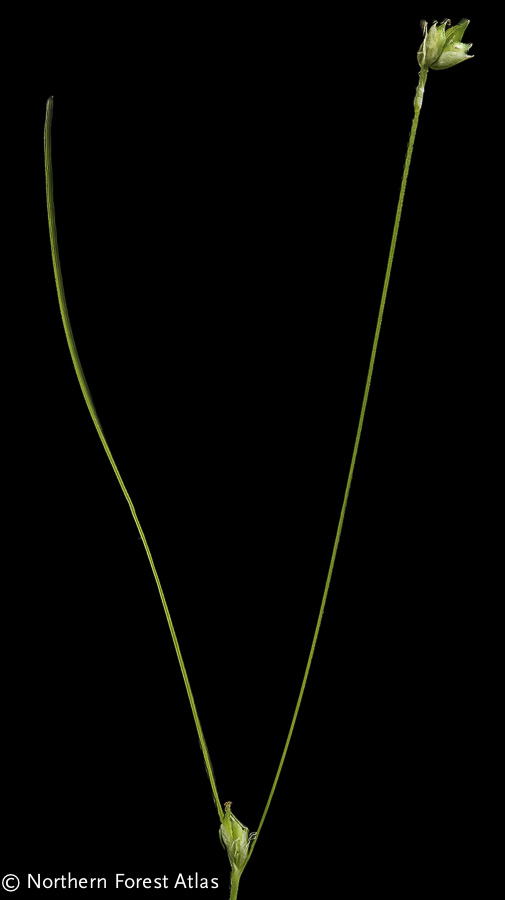

Brunnescens and trisperma are closely related and can grow together. So far as I know, they can’t be told without flowers or fruits. In brunnescens, the spikes are close together, the perigynia numerous, and the lowest bract shorter than the infloresence.

In trisperma, there are a few widely separated spikes, each with onloy a few perigynia, and the bract is about as long as the infloresence.

The fourth upland sedge along the Bourne Pond trail is Carex leptonervia. It has broad, shiny leaves, and, unlike debilis and intumescens, no red on the leaf sheaths.

It is much less common on the plateau than the other three, and needs, I think, somewhat more fertile soil. The flowering stalks are long, with broad bracts. The flower clusters are slender, but do not droop like those of debilis.

In addition, the leaf edges have small, downward pointing hairs just above the sheath. This is a unique feature; in other sedges the leaf margins are smooth, or have all upward-pointing hairs. Several related sedges occur on fertile soils in the valleys; but, so far as I know, leptonervia is the only one on the plateau.

Sedges in Shaded Wetlands With Mineral Soil

Trails often cross streams and small forested wetlands. Where the wetlands are peaty and have sphagnum moss, the common sedges are Carex trisperma and brunnescens, shown above. But where there is mineral soil and seepage, as in a ditch or along a brook, there are two characteristic large sedges.

Both occur at this brook crossing. Most of what you see is Carex scabrata. It is a creeping species and makes large patches. The leaves are rough on the edges, the veins, and the surface; it is our only large northern sedge that is rough everywhere.

Most of the stems in any patch are often sterile. It fruits well in the sun, but only sparsely, if at all,in the shade. When you find a fertile one, it has erect, cylindrical spikes, and a single male spike on a long stalk. The spikes are down among the leaves and not particularly conspicuous.

With it, not conspicuous here but very common overall, is Carex gynandra, a clump-forming species. The leaves of the two look very similar. Here is a large patch of gynandra along the edge of a wet wood road in New York.

The fruits of scabrata and gynandra are quite different. Gynandra has long dangling spikes with needle-tipped scales. It fruits abundantly, and remnants of the spikes can be found late in the year.

The most useful vegetative differences are that the stems of gynandra are clumped, rather than spread in a patch; the leaves are rough on the edges but not the surface; and the spikes dangle and have long, needle-tipped scales.

The photo shows the northeast meadow at Branch Pond. The broad-leaved grasses and sedges, dead snags, sharp forest edge, and deciduous shrubs (in this case meadowsweet and steeplebush in the foreground) are all beaver meadow signatures. Here is closer view.

The soil is peaty, and has a continuous sphagnum sphagnum cover. The dominant sedge here is Carex utriculata . It is tall, broadleaved, shiny, and forms extensive patches. Only a few stems fruit. The fruits are thick, cylindrical, and erect or slightly leaning.

In mid-summer the utriculata meadows start to turn yellow. Several other sedges have similar fruits, but all are tussock-formers rather than creepers, and none form large continuous stands.

Isolated hummocks, often with snags, occur in this part of the meadow. Here is one with St. Johnswort, narrow-leaved gentian, cinnamon fern, and wild raisin. The hummocks are likely remnnts of whatever sort of peatland—bog or swamp—was here before the beaver came.

Channels and pools, either created by the beaver or remnants from the previous wetland, are common. Three-way sedge, Dulichium arundinaceum is a common dominant. It grows in the wetest places: pools, channels, areas of flooded peat.

Dulichium is a creeper and tends to form pure colonies. The short, upswept leaves in three rows are unique.

If we had to classify these lower portions of the meadow, we might call then medium fens. They have, on the one hand, peaty soils and a continuous layer of sphagnum; but, on the other, enough flooding or seepage to have tall, broad-leaved grasses and sedges and deciduous shrubs.

The upper portions of the meadow, to the east, are quite different. They are more boggy, with shrubby thickets and narrow-leaved sedges. Here, for example, the dominant sedge is Virginia cottongrass, Eriophorum virginicum.

The boggy upper edge of the meadow is quite shrubby: here, for example, the tall shrubs are mountain holly, arrowwood, and wild raisin; the lower, browner one is leatherleaf. This is a very common combination in boggy thickets everywhere. The grey-green grass in front of the shrubs is bluejoint grass, Calamagrostis canadensis. It is common here, but not as dominant as it might be on mineral soil.

Eriophorum virginicum is our commonest cottongrasses, found in open, wet, peaty bogs and meadows of all sorts. It is a creeper that has shiny leaves and makes large patches. The leaves are relatively short, and less visible than the fruiting stems.

The heads are compact. They start white, turn tawny, and bleach white again. The cotton is the long hairs that surround the seeds.

In the upper parts of the meadow, the cottongrass mixes with Carex magellanicum, a pretty but less conspicuous sedge, grows mixed with it. Its leaves are shorter and duller, and I haven’t gotten good pictures of them yet. The fruiting stems, however, are strikingly pretty. The fruits are compressed, in dangling clusters, and the scales have long tips.

Magellanica is the last major sedge of the beaver-bogs. A few others occur here, but they are more characteristic of pond shores and floating bogs, and I will deal with them in a second article.