The Northern Forest of northeastern North America extends from eastern Maine and the Maritimes to the edge of prairies in Minnesota and Manitoba. It contains, besides forests, beaches, barrens, cliffs, marshes, swamps, bogs, farms, grasslands, lakes and ponds, and, on the highest eastern mountains, small amounts of krummholz and tundra. It is large, diverse, and surprisingly continuous. By any standard it is a great forest. In a world in which much forest has been lost or damaged, and where natural carbon storage is critical to the future of the planet, it is also a very important one.

The continuing importance of the forest depends on its integrity and health. Given the threats of the coming century—population, pollution, climate disruption, resource extraction, disease—neither can be taken for granted. Its survival will depend both on its resilience and our stewardship. It has, after three hundred million years of evolution, remarkable endurance and flexibility. We have, if we choose to use them, equally remarkable abilities to observe, appreciate, and protect.

The Northern Forest Atlas was created to document the current biology of the forests and to provide tools for the next generation of naturalists and conservationists who will study and protect them. The Atlas was conceived by Ed McNeil and Jerry Jenkins in 2011, and began full-time operations in 2013. It has three main goals: to create a library of photos and air videos showing the landscapes, plants, and animals of the northern forest; to create photographic and diagrammatic atlases, both paper and digital, for plants and landscapes; and to design and produce a series of modern field guides to plants and ecology.

This website documents about 900 species, and contains 5,000 online photos, 65+ videos, four Digital Atlases totaling 3,300 pages and containing about 8,000 images, plus more than 25 large-format charts. The imagery currently includes woody plants, mosses, sedges, grasses and landscapes. Many are available for free download from the website, and may be used for any personal, educational, or nonprofit use. We also have for sale, book-length Photographic Guides and Folding Charts for mosses, sedges, grasses and woody plants, produced in partnership with Cornell University Press, containing about 400 pages and 900 species.

We recently completed a Photographic Guide and a Digital Atlas of grasses. Our first ecological field guide, to woody plants, is in progress and scheduled for publication early in 2025. Beyond, we are planning a guide to ecological patterns.

Woody Plants: Black Ash, Allagash River, Me

The imagery on the website also documents our progress towards our central technical goal: to provide sharp images at scales ranging from landscapes to near microscopic. To do this we use a range of techniques—focus stacking in both the studio and the field, high-dynamic-range composites, 4k-6k air video-that are relatively new and have radically changed the capabilities of nature photography.

For aerial photography, we use a custom-built, high-wing amphibious floatplane, the AirCam, fitted with video cameras on nose and wing vibration isolating mounts. The pilot sits in the front seat and controls the cameras; a second photographer sits in the second seat and shoots hand-held stills. We also use high capability drones with 4 to 6k hi-resolution cameras.

For close-up and macro photography we use a portable studio with led lighting and a computerized focussing rack. In the field we use shades, diffusers, reflectors and portable lights. We typically shoot stacks of twenty to eighty images in the studio and ten to fifteen in the field. When processed, these give us great clarity and depth. This enables us to show details that have not been imaged before.

At medium scales where we can’t control lighting, we usually shoot sets of three to five images at different exposures and merge them digitally to produce high-dynamic-range composites. This allows us to shoot high-contrast scenes, like the hemlock forest below, and preserve critical detail in the shadows.

Once we have imagery at different scales, we have to interpret it and interconnect it. We do this with structural and ecological diagrams, particularly in our digital atlases and books.

Here, from the Digital Atlas of Northern Forest Bryophytes, is a studio photo of the moss Bryhnia novae-angliae, plus diagrams showing its diagnostic features and habitat.

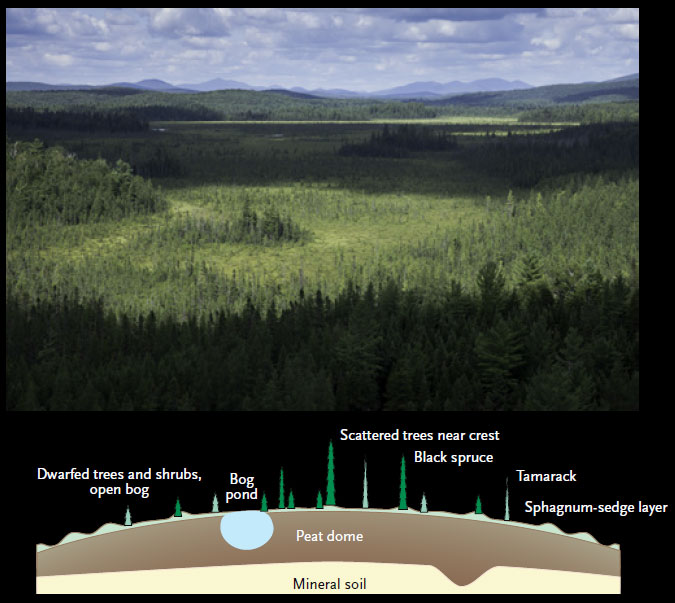

At large scales we use ecological diagrams to show how typography, soil, and vegetation types create the patterns we see from the air. This diagram of a large open peatland is from the Digital Atlas of Northern Forest Landscapes.

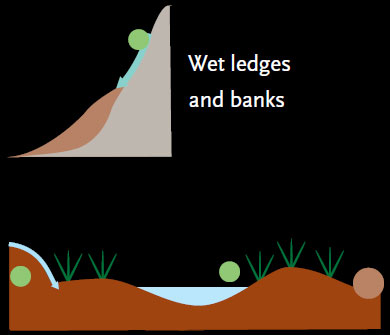

At intermediate scales, we diagram the species within individual communities, to show their structural roles and how they are arranged. This diagram of a river-shore meadow is also from the Digital Atlas of Northern Forest Landscapes.

For more on photographic technique, see our articles on Air photography, Stacking in the Studio, and Stacking in the Field in the articles section of this site. For an explanation of northern forest landscapes, download our Northern Forest Trees by Habitat, All Northern Forest Landscapes, on page 2 of Products.

I just came across your project and the book to be published next year. It is, in a word; brilliant.

Given that much, if not most, of the forest is in Canada, are you cooperating within any group or individuals here to help further your aims and development of videos, books, etc.?

Regards,

Ross

Hi Ross,

Much of the Northern Forest is in the US, stretching from coastal Maine and Nova Scotia to the prairie edge in Minnesota and encapsulating the Great lakes with it’s southern boundary defined by the northern limit of oak-hickory forests. We have worked with WCS Canada’s Toronto office and have a major donor in Canada. We also are using several Nature Conservancy Canada folks for species location knowledge. The Woody Plants Photographic Guide and the upcoming Woody Plants Field Guide should probably be in the hands of everyone at the Canadian Forest Service. If you have ideas for distribution we should pass on to Cornell or others, please let us know. All of the publications from Cornell University Press will be available on Amazon as well.

Cornell University Press is distributing the Woody Plants Photographic Guide to some retail locations in Canada I’m told. FYI, the Sedge Photographic Guide will be out in April of 2019. We are about 6 years into an 11 year project and more publications will be coming out annually. Much of the hard work is done, and writing, photography, graphics and field work for sedges, grasses, mosses and herbs will occupy us for the remaining four to five years. We plan a book on forest ecology near the end.

Ed McNeil

How far north does your project encompass? I live in North Bay, Ontario and I am wondering if includes that area. If not, I doubt very few species will be missing in your guides for my area from what I have seen.

Yes Brent, North Bay is within the Northern Forest. We have been filming near Elliot Lake, on Manitoulin Island, and Kilarney this past summer and have more work to do in that area over the next year or so.

Thank you for advancing the state of the art in field guides – much of your work is better than what out there and will be of great use to amateur naturalists in the area. I intend to get the sedge guide, I am hoping for a grass guide and I am seriously considering the Woody Plant guide.

Does the scope of the project go as far as North Bay, Ontario? This area is on the Precambrian Shield in Zone 3, and is near the boreal forest. (I apologize for a potential double post, my last posting may not have gone through due to incorrect NoScript settings).

Cheers, Brent

Hi, I live in Northwest Ohio. I couldn’t find anywhere that talked about this book covering plants from Ohio.

Can you help me out?

Bradley

Hi Bradley, Ohio is mostly south of the Northern Forest, although there is a lot of commonality in Sedges, Mosses, and Herbs. Less so for Woody plants, but still many in common. Ed

I think this is really great work you’re doing. One thing I came to this tab hoping to find, though, is a clearer definition of what you consider to be the coverage of the “northern forest,” like some of these other commenters- but on the southern end. The rough graphic with a blue-green range is suggestive, but as I live within that patch of blue-green I feel like some things are missing. Perusing the Woody Plants Atlas I scrolled down to where Magnoliaceae ought to be and was surprised to find it wasn’t there. Liriodendron tulipifera and Magnolia acuminata are both local to dominant in forests on the Allegheny Plateau in NY state (often well away from the oak-hickory tension zone) within what would seem to be the range on the existing graphic, and would seem as necessary to include as other mainly-southern species with limited northern occurrence like Sassafrass or Scarlet Oak. On the atlantic slope and the western great lakes/carolinian ontario both species do seem more tightly restricted to more southern-affinity zones, but in WNY they often occur in Hemlock-Northern Hardwoods forests well up into northern-affinity parts of the plateau. Maybe a clearer map graphic would help clarify some of these questions?

I am a question very similar to Erik’s. I am interested in the Western Catskills. Are your areas of study sharply defined?

Thanks.

Sharply defined? No, these boundaries are more often broadly defined, sometimes ill defined, but species mix will give you a general idea of where the boundary is. Forest/prairie is easy, southern limit of the Northern Forest is more variable. Ed

You all have done amazing work and I will be purchasing all of your books for sure. I just got Mosses and discovered your website and am blown away. I live in the Pacific Northwest and would like to know how much overlap there might be with the East and West. The forests are somewhat similar but we do get a lot more moisture here and or geology is different but there does seem to be a great number of common species, if maybe slight variations. Again, I am thrilled and amazed at what you have done.