Jerry Jenkins

The central goal of the Atlas Project is to make tools—guides, charts, atlases—for people to teach themselves natural history and ecology. As a way of testing them, and having a lot of fun in the process, we hold occasional classes and camps. We give out tools, pose problems, go to interesting places, and do field and lab work. Along the way we may coach a bit or give a few hints but we don’t teach much. If the tools work the way we should, we don’t have to. If they don’t, we have to make them better.

In July, we held an Atlas moss camp in Rowe, MA. That’s Sue Williams’ house, and my camper and mobile lab. We invited some very good people, and ended up with a very hot group.

Here’s Aaron, Matt, Erik, Somebody’s hat, and Lisa.

Linda, Elizabeth, , and Aaron working the woodland mosses that live in the grass in a shaded lawn.

Sue, Aaron, Linda Erik and, behind, Elizabeth, i the channel of Pelham Brook.

And Brett, Lisa, and Matt, also in the brook channel.

We provided the students with, and asked them to test, a variety of graphic tools. For preparation and as crib-sheets in the field, they used moss maps.

And photomosaics showing common species and their habitats

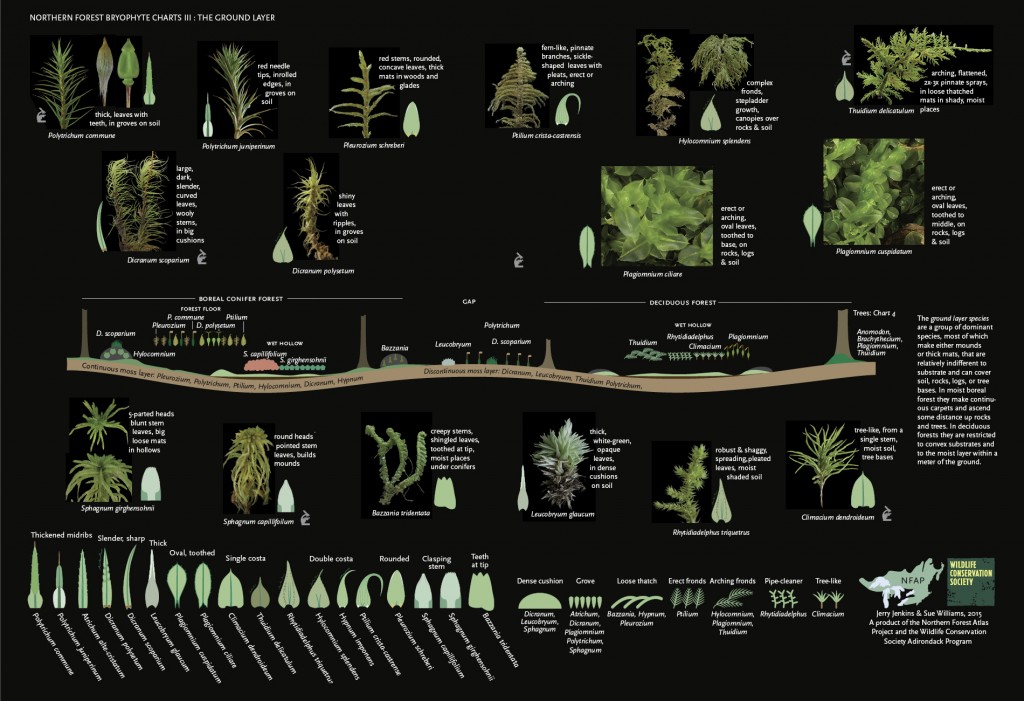

For lab work, they used two large charts of the Northern Forest moss genera. Here’s the first one:

The advantage of a big chart is that anything you find is somewhere on it. They also used smaller charts for details:

Some of these charts are on the Graphics page. Others are still under development and will appear as we get them finished.

The course was structured around common habitats and common mosses. We started at Sue’s house, doing a shady lawn and second-growth woods, and then worked outward, doing older woods, a wooded swamp, a ledge and boulder-field, and a stream channel. In five days, without going more than two miles from the house, we were able to see over half the common mosses in the Northern Forest.

Here is the swamp:

And some swamp mosses. Sphagnum squarrosum and girgensohnii:

Rhytidiadelphus squarrosus and Aulacomnium palustre:

And Polytrichum pallidisetum and Thuidium delicatulum:

Here, for contrast, are two related species, Polytrichum commune and Rhytidiadelphus triquetrus from Sue’s lawn.

Pelham Brook is the outlet stream from a dammed lake. It has a nice rocky channel but rarely floods or rolls rocks, and so even the small rocks have (small) mosses.

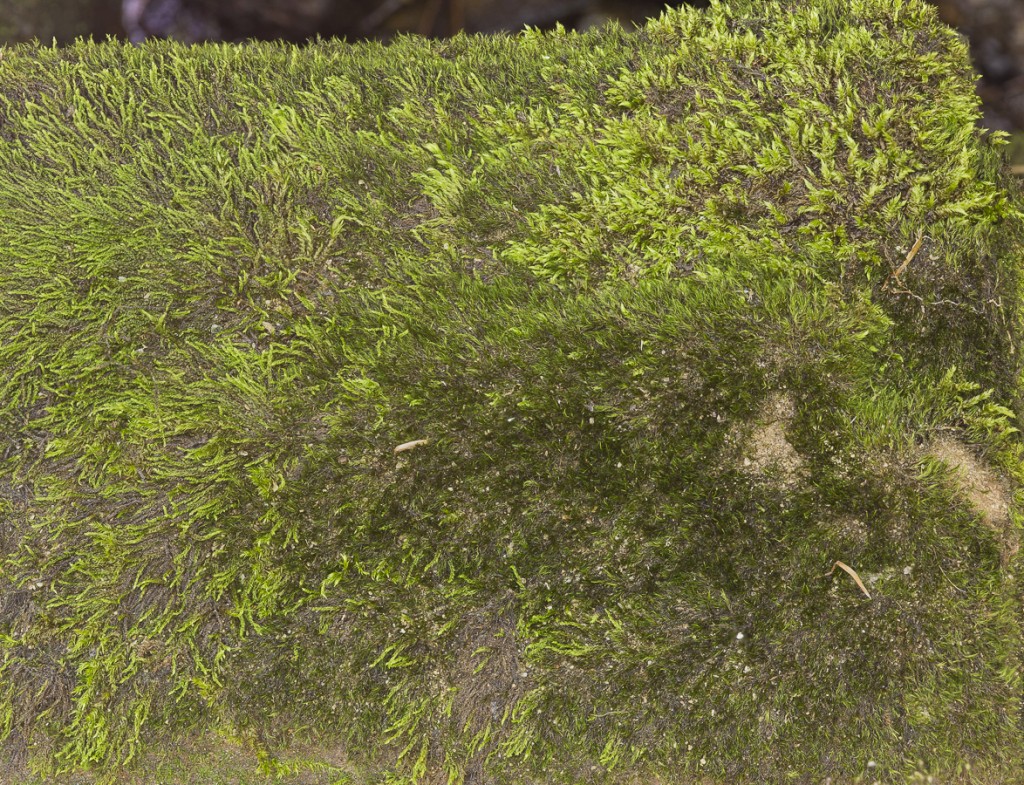

The brook mosses were interesting. The normal small-stream dominants were all there, and in quantity. Here’s Bryhnia novae-angliae:

The broad stem leaves, open branching, and twisted tips of the branch leaves are all good characters.

Here’s Hygrohypnum eugyrium, one of the commonest mosses in small streams. It is damnably hard to identify in the field. The concave leaves with curved tips are suggestive, but other things have them as well.

Mixed with the common things were some much less common ones. The light stuff on this rock is Hygrohypnum ochraceum.

The dark stuff is a mixture of two small stringy species: the slender-leaved Blindia acuta, uncommmon with us:

And the concave-leaved (and bordered!) Platylomella lescurii. either rare or hard to recognize, or both.

So much brightness and pleasure in tiny things. And puzzlement too. We wish we knew why they are in this stream and not in many others. But we don’t.

Or which ledges we were going to see the tiny Rhabdoweisia crispata on, and which not. Or for that matter, how to take a clearer photograph of it.

That, in brief was Moss Camp 016. It was wonderful and sunny and we miss it. We are planning another moss course next June at the Eagle Hill Institute, and perhaps either a sedge camp or a limy moss camp in Vermont. Watch for news.